What is Dyslexia?

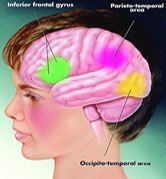

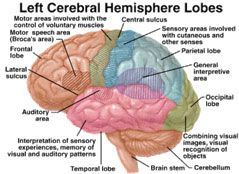

The origin of dyslexia is neurological, affecting the temporal lobe and cerebellum regions of the brain. These areas of the brain are responsible for descrambling sound-to-symbol correspondences (Shaywitz et al., 2004). According to Shaywtiz, Shaywitz and Liberman (1991) readers who do not have dyslexia rely on their temporal lobes to descramble and decode sound and symbol relationships. Dyslexic readers’ prefrontal and frontal lobes of the brain are activated for the purposes of processing sounds to their corresponding symbols—the process of reading.

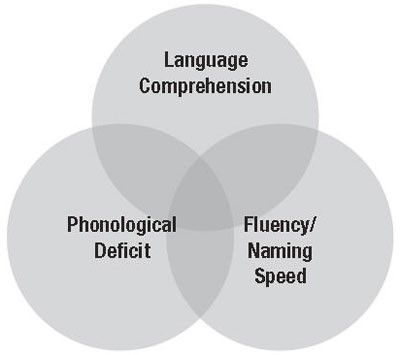

On a case-by-case basis, individuals with dyslexia have difficulties with all three components of language (i.e., phonology/sound, fluency with word accuracy, reading rate and language comprehension). When all three components of language are affected, a “reading bottleneck” is produced (Fletcher et al., 2007) and the child meets numerous challenges when reading, writing, spelling, math and memory-related learning are required for growth in reading.

Individuals with dyslexia do not have low IQs.

Dyslexia may be inherited, but individuals with dyslexia do not have low IQs or learning disabilities. In fact, millions of individuals with dyslexia are gifted or have above-average intelligence. The cerebral cortex or “thinking brain,” can be trained to function in a compensatory role to descramble and encode incoming sounds and symbols.

There is a plethora of research on dyslexia.

According to Shaywitz (2003), there are several indicators that a student has a specific phonological (sound or symbol) weakness, such as individuals with “dyslexia”. Dyslexia is a specific reading disorder that affects over 40 million American children and adults. According to current research, “dyslexia is both prevalent and widespread. It is the most common subtype of learning difference, affecting from five to ten percent to fifteen (Roongpraiwan et al., 2002) to twenty percent of our population of learners (Shaywitz, 2003).”

Typical Symptoms of Students Who Have Specific Phonological (Sound-Symbol) Weaknesses

- Reading that is slow and effortful, choppy and hesitant, with omissions and substitutions of words?

- Mispronunciations, confusions, articulation errors or talking around words

- Spelling is poor and words are written as they sound. Handwriting, poor grades and test scores are affected by reading difficulties.

- A family or genetic predisposition to reading difficulties

- Self-esteem and embarrassment when reading aloud are required in school or social settings.

- Avoiding speaking situations in school and group settings

- Reduced motivation to read because reading is a struggle and learning seems difficult

Evidence and Related Co-Existing Problems That Your Child is Struggling to Read

- Faulty grip and letter formation

- Attention problems

- Anxiety

- Task avoidance and weak impulse control

- Easily Distracted

- Problems with comprehension of spoken language

- Confusion of mathematical signs and computation processes

- About 30% of all children with dyslexia also have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

If your child exhibits one or more of the above symptoms, he or she may be at risk for reading problems or have a specific reading disorder that is phonologically based.

What is an At-Risk Reader? And

Which Students are At-Risk for Reading Problems?

At-risk readers are children who have difficulty with reading. The cause of their reading problems results from a variety of factors, which can determine which research-based methods and interventions will be implemented to increase their skill in reading and close their learning gap.

Students at-risk who struggle with reading in grades K–4 have individual reading profiles but can represent one of the four categories of causation or reading problems:

- Late-Emergent Reading Disabled Students: Students with this profile demonstrate normal progression in reading development as their K–3 same-age peers in the early grades when the reading demands are not too great. They also respond positively to early Tier 2 reading intervention. However, as they transition to each successive grade level, greater reading proficiency in phonemic awareness is necessary for fluency and accuracy. As the reading content becomes more complex, these children are faced with greater challenges in reading, writing, spelling and comprehension (Compton, Fuchs, Elleman, & Gilbert, 2008).

- Instructional Casualties: Instructional casualties result from schools that do not place a strong focus on improving reading instruction in grades K-3. Not all schools have strong reading programs in place, resulting in students who may not have received adequate reading instruction in the foundational skills of reading. These students will require reading intervention and supplemental support in the later grades to catch up and close the reading gap (Vaughn et al., 2008).

- English Language Learners: English Language Learners are becoming one of the largest subgroups of readers at-risk for reading difficulties. In the past decade, the number of English language learners has increased by 57% (Maxwell, 2009). English language learners need intensive reading support in all five critical areas of reading (e.g., phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension). English Language Learners are students at-risk for reading difficulties and are a large subgroup of students who may enter school significantly behind in the fundamental skills of reading. ELL students show weaknesses in oral language knowledge necessary for reading comprehension. They also demonstrate limitations in their phonological and print-related knowledge required for learning to read words. It is necessary to provide direct and explicit instruction in how letters and sounds relate to making words, along with opportunities to practice these relationships by reading texts that are culturally meaningful for second language learners. All schools must increase their support of English language learners by providing English language development instruction and intervention to meet the needs of these students. English language learners continue to be at-risk for reading problems.

- Preadolescent and Adolescent Older Students Requiring Ongoing Intervention: Students who received intervention in their early grades may make progress in acquiring the foundational reading skills, but they cannot read with the proficiency necessary to meet the challenges of literature in their higher grade levels without ongoing intervention. These students require continued intervention in order to be successful in their classes and reach grade-level benchmarks. Greater than 25% of 8th-grade students and more than 33% of 4th graders do not read well enough to understand important concepts and acquire new knowledge from grade-level texts. For students with learning disabilities, the numbers are of greater concern.

Adolescents are Rarely Identified and Supported for Literacy Intervention

Vocabulary and comprehension are not the primary causes of the underlying reading problems of older students (Catts, Hogan, and Adlof, 2005). The fact that universal screening for reading problems among students at the secondary level is usually never implemented results in older readers not being identified for reading intervention and support.

Preadolescent and adolescent students continue to struggle with reading complex texts across all content area classes, which results in:

- Scoring low on state and district-required tests

- Taking these tests numerous times to meet graduation requirements

- Scoring extremely low on college ACT and SAT tests, which limits college options and

- Scoring is extremely low on college tests, which reduces or limits scholarship funding.

The assessment of older students has been investigated in numerous studies. Evidence has found that

older students who struggle with reading continue to have problems with comprehension, decoding, and/or fluency. Many of these students can be identified with screening tests of word-level reading skills, fluency and comprehension (Compton et al., 2008; Hernandez, 2011; Lipka et al., 2006; Snow and Biancarosa, 2004; 2006; Vaughn et al., 2008).

Students whose performance is moderately to significantly below grade level on a reading inventory or below the 20th percentile on a reading benchmark assessment will require more intensive interventions. Intensity is not just increased by manipulating minutes per session and days per week. The type and quality of service delivery provided must systematically and sequentially teach reading skills, which are scaffolds, so that critical weaknesses are targeted and learning is cumulative to close learning gaps and normalize reading deficits.

Even though your child may be in the 4th grade or higher, she or he may continue to struggle with reading assignments in school because reading texts becomes more challenging for each higher grade level. This literary requirement presents a challenge for the student who has a reading disorder or struggles with decoding multi-syllable or unfamiliar words. When students find reading difficult or challenging, comprehension is reduced, resulting in lower grade performance and a greater degree of frustration, leading to a lack of motivation to read.

In most educational settings, small group instruction does not produce the greatest gains in academic achievement due to:

- The number of students within one classroom with varying learning abilities

- The number of students who must receive differentiated instruction within the same classroom

- The time involved in administering assessments and monitoring progress for each student

- The cost of providing additional professional support specialists

At Gifted Apples, we look forward to meeting you and your child.

Call 216.820.3800 or 440.755.9125

Email ljfarmerr.lf@gmail.com for details about our Literacy Intervention programs.

Sincerely in Reading,

Loretta J. Farmer, BA-SLP, MEd., Principal

Our goal is to provide intensive literacy instruction to preadolescent and adolescent students who require specialized intervention in reading and math. We support post-high school adult literacy education.

References:

Biancarosa, C. and Snow, C. E. (2006). Reading Next—A Vision for Action and Research in Middle and High School Literacy: A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York (2nd ed.). Washington, D. C.: Alliance for Excellent Education. Retrieved June 2, 2016 from: https://www.carnegie.org/media/filer_public/b7/5f/b75fba81-16cb-422d-ab59-373a6a07eb74/ccny_report_2004_reading.pdf

Catts, H. W., Hogan, T. P., & Adlof, S. M. (2005). Developmental changes in reading and reading disabilities. In H. Catts & A. Kamhi (Eds.), Connections between language and reading disabilities (pp. 23–36). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Compton, D. L., Fuchs, D., Fuchs, L. S., Elleman, A. M., & Gilbert, J. K. (2008). Tracking children who fly below the radar: Latent transition modeling of students with late-emerging reading disability. Learning and Individual Differences, 18, 329–337.

Hernandez, D. J. (2011). Double Jeopardy: How Third-Grade Reading Skills and Poverty Influence High School Graduation. A new report from the Annie E Casey Foundation. Retrieved July 8 2016 from: http://gradelevelreading.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Double-Jeopardy-Report-030812-for-web1.pdf

Hinton, C.D. Primer on Dyslexia-Dyslexia Primer

Retrieved February 15, 2016 from: http://www.oecd.org/edu/ceri/primerondyslexia.htm

Fletcher, J.M., Lyon, G. R., Fuchs, L.S., Barnes, M.A. (2007). Learning Disabilities: From Identification to Intervention. New York: The Guilford Press retrieved from: http://support.lexercise.com/entries/258401-Fletcher-Lyon-Fuchs-Barnes-2007-Ten-General-Principles-for-Instructing-Students-with-LDs-

Lipka, O., Lesaux, N. K., & Siegel, L. S. (2006). Retrospective analyses of the reading development of grade 4 students with reading disabilities: Risk status and profiles over 5 years. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39, 364−378.

Maxwell, L. (2009, January 8). Immigration transforms communities. Education Week. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

National Association of State Boards of Education. (2005). Reading at risk: How states can respond to the crisis in adolescent literacy. Alexandria, VA: Author.

Roongpraiwan, R., Roongpraiwan, N., Visudhiphan, P. & Santikul, K. (2002). Prevalence and clinical characteristics of dyslexia in primary school students. J. Med. Assoc. Thai., 85(4), pp.1097-1103.

Scottish Rite Hospital. Orthographic Processing: A Subcomponent, Not A Subtype, of Developmental Dyslexia

Retrieved February 3,2016 from: https://www.tsrhc.org/TSRHC/medi/Media-Library-Files/PDF/Position-Statement-and-Remediation_rev11212014.pdf

Shaywitz, S., & Shaywitz, B. (2006). The Neurobiology of Reading and Dyslexia. National Center for the Study of Adult Learning and Literacy. Retrieved February 11, 2016 from http://www.templatezone.com/marketing2006/Temp/Carol/carol.htm

Shaywitz, S. E. (2003). Overcoming Dyslexia. Random House Inc., NY.

Shaywitz, B. A., Shaywitz, S. E., Blachman, B. A., Pugh, K. R., Fulbright, R. K., Skudlarski, P., Mencl, W. E., Constable, R.T.,Holahan, J. M., Marchione, K. E., Fletcher, J. M., Lyon, G. R., Gore, J. C. (2004). Development of left occipito-temporal systems for skilled reading in children after a phonologically-based intervention, Biol. Psychiatry, 55, pp. 926-933. http://www.templatezone.com/marketing2006/Temp/Carol/carol.htm

Shaywitz, S. E. (2003). Overcoming Dyslexia. Random House Inc., NY.

Retrieved Feb 3, 2016 from: http://www.templatezone.com/marketing2006/Temp/Carol/bb_Feb2006_large.jpg

Vaughn, S., Fletcher, J. M., Francis, D. J., Denton, C. A., Wanzek, J., Wexler, J., et al. (2008). Response to intervention with older students with reading difficulties. Learning and Individual Differences, 18, 338–345.

Retrieved on 04-01-2016 from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2614270/

Send Us a Message

Send us a message using the form below or call us at 216-820-3800. We will respond to your inquiry as soon as possible.

Thank you for submitting the form. I will respond to your message within 24 - 48 hours.

Please try again later

Tutoring

Contact Information

Gifted Apples Reading and Math PreK–12, LLC, is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization

Business Hours

- Mon - Fri

- -

- Saturday

- -

- Sunday

- Closed

All Rights Reserved | Gifted Apples Reading & Math